Tiny Food Worlds: An Interview with Christopher Boffoli

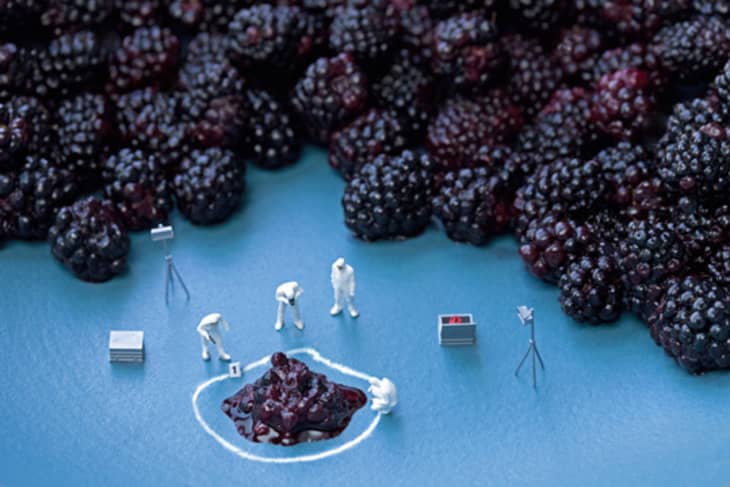

Tiny toy figures are hard at work in a world of giant food in Chris Boffoli’s photography series Disparity. Humorous and occasionally dark, the scenes depict food in a way that is both beautiful and a little monstrous. The Seattle-based photographer, food writer and avid cook spoke with us about his creative process, the ingredients he works with, and his thoughts on Americans’ relationship with food.

What inspired you to use food as the backdrop in this series?

Food seemed like a perfect backdrop. It can be very beautiful in terms of color and texture, especially when photographed with macro lenses and natural light. Food is also something common to everyone in the world. Regardless of your culture, language and social status, food is usually something that is instantly familiar to us. In mixed company everyone can talk about food without controversy. So along with the figures (which are essentially toys and also globally common) I figured it would make the work broadly accessible.

From the start the project was also intended to be about the excess of America. Where else would the idea of a piece of towering chocolate cake seem right at home than the land of the Big Gulp and the all-you-can-eat buffet? We live in a land of tremendous bounty. But at the same time I don’t think we take responsibility for that bounty in the context of the greater world, not to mention its impact upon the environment.

What was the creative process? Does the food inspire the scene? Or do you come up with your ideas before buying the ingredients you need?

I will sometimes sketch out the ideas in advance. But most of the time it starts with the food. I try to work with what is in season and what’s fresh. Sometimes I’ll scan the local farmers market to see what looks good. Then I’ll bring the food back to the studio, clean it, cut and style it, and compose the shot. There is a lot of cheating in commercial food photography, like the way that white glue is used in place of milk, or glass cubes are used to stand in for ice. But from the start I made a decision that everything in my images would be edible and real, right down to the agave nectar and wheat-based putty that I use to stand the figures in place.

I try to use available light as much as possible with this series. We have a lot of overcast skies here in Seattle, which produce what I think is beautiful, even light that is well-suited to food photography. I’ll usually set up the food, arrange the figures and then spend the time working out different perspectives and angles on the scene. I use reflectors to change the light on the scene and then will try various fields of focus until I’m happy with the shot.

This kind of photography looks simple. But it can actually be very tedious and tricky to shoot, especially working with tiny figures that often have a mind of their own and that are constantly falling over and needing to be reset.

What do these images say about Americans’ relationship to food and consumption?

Well, a common reaction to some of the images is for people to say, “I wish I were that person in the scene with a wall of Oreo cookies.” So that’s the fantasy. But in reality, even our favorite foods would quickly become repulsive to us if we were burdened with eating a mountain of them. But again, what is more American than ever bigger, ever more food? It is not enough for us to have one doughnut. We sell them by the dozen. So part of the work is about our passion for consumption and the voraciousness of our desire for food.

I was also thinking about the extent to which we’ve become food spectators in America. Every year there are mountains of new cookbooks released. And we have entire cable television networks devoted to food and cooking shows at the same time when many of us are eating pre-cooked, processed foods in our cars. It was at once shocking and horrifying to see part of Jamie Oliver’s TV show, on his initiative to reform school lunches in LA, in which kids were so used to eating foods only in processed form that they were unable to identify common vegetables.

We live in a country of tremendous bounty and yet we have these dysfunctions when it comes to food and its role in our culture and society. It is just interesting to me on so many different levels.

Do you cook? How would you compare the process of taking these photographs with cooking?

I do cook and bake quite a bit. I have commercial-grade kitchen appliances in my home studio. I also write about food for magazines here in Seattle when I’m not shooting pictures. I’m half-Italian so to some extent I think an ardor for food is hard wired into my DNA. I’m the oldest of 3 kids and I was fortunate in that I had the good sense to cultivate close relationships with my grandparents from an early age. They were great cooks and I paid attention to what they taught me. My paternal grandfather was a first generation American. He only got as far as the eighth grade. But when it came to making pasta sauce he intuitively understood the chemistry of what made that sauce function.

Cooking, like writing or shooting photographs, is a creative outlet. It is just a matter of engaging different senses, but they’re informed by the same core.

Christopher Boffoli has a January 2012 show coming up at Winston Wachter Fine Art in Seattle. He has also recently released a limited printing of greeting cards with photos and captions from the Disparity series.

• See the full series: Disparity at Christopher Boffoli’s website

• Get the greeting cards: Disparity Limited Edition Greeting Cards

Related: The Art of Vegetables: Camera in the Cupboard

(Images: Christopher Boffoli, used by permission)